In 1967, the year before Dance of the Happy Shades was published, I met Alice Munro in a Unitarian Church hall in Victoria, BC. I was there as part of the local Unitarian church’s youth group, Liberal Religious Youth (LRY). I had joined because my then-boyfriend and his family were members of the church, and he assured me that the LRY was both liberal and young, but not terribly religious. This proved true; many happy Sunday mornings were spent throwing the I Ching, listening to Hendrix and the Rolling Stones, discussing the true meaning of “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” and “White Rabbit,” and debating whether to drop acid on an upcoming trip to an LRY conference in Seattle. LRY was disbanded in 1982, possibly with good reason.

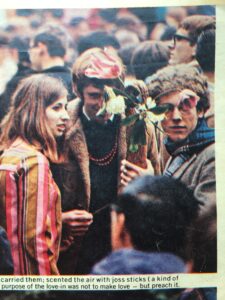

Once a year, the Sunday service was given over to the LRY. That particular Sunday in June was also the day of a Love-In in a nearby park. It was the “Summer of Love” and my boyfriend and I planned to attend the Love-In, but first we had to participate in the service. The group had decided to try and recreate the spirit of our basement meetings, with readings from the Tibetan Book of the Dead (instead of a sermon), and a heartfelt choral rendition of the Byrds’ “Turn, Turn Turn” (for a Biblical element). There was also some spoken word poetry, and one interpretive dance. That’s where I came in.

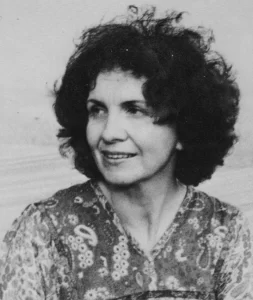

I danced alone, wearing an outfit my mother had recently made for me: Bell bottom pants and a top with belled sleeves in striped French cotton in shades of olive, pink and black. I don’t remember what music I danced to (possibly “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” which had just come out), but I do remember a lot of ecstatic hair-tossing. Afterwards, the LRY served coffee, tea and cookies (baked by our moms) to the congregation. I passed a plate of cookies to a woman with a head of dark curls. As she took a cookie, she smiled at me and said, “I enjoyed your dance. I wish I could dance like that.” I thanked her and moved on with my plate of cookies, happy to know that my youthful enthusiasm had been appreciated by an older person. I had just turned 17. Alice Munro was 35.

The following year, Dance of the Happy Shades was published to huge acclaim, and I realized that the woman who had been so kind to me was the Alice Munro. After I read Dance of the Happy Shades, I was in Munro’s Books (buying the latest Iris Murdoch novel, no doubt). As Alice put the book in a bag for me, I congratulated her and asked how she found the time to write (somehow I knew she had children). She laughed and said something along the lines of “When the older ones are at school, the baby is napping and I’ve caught up on the laundry.” So—kind and modest as well as enormously talented (and probably a perfectly decent dancer).

What struck me at the time was that 1) writers are real people and 2) women writers often have children to care for, laundry to do, careers, and few hours in which to write. Much later, I realized that not only had Alice Munro’s casual remark led to my first feminist thought, it also helped me understand that being a writer was not beyond my reach. I finally started writing in my fifties, when another icon of Canadian writing told me I should be writing children’s books. But that’s a story for another time.